- Home

- Shelley Harris

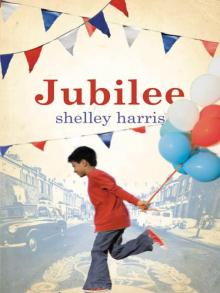

Jubilee

Jubilee Read online

For Alex: this, and everything else

Contents

Cover

Dedication

Title Page

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

One Two-Hundred-and-Fiftieth of a Second

Acknowledgements

Copyright

‘I will provide you with the available words and the

available grammar. But will that help you to interpret

between privacies? I have no idea.’

Brian Friel, Translations

Prologue

One two-hundred-and-fiftieth of a second

The photograph in front of you was taken in one two-hundred-and-fiftieth of a second. Your first thoughts, when you look at it, are of the decades that place themselves between you and it – what a museum piece it is! How retro, what a laugh – the haircuts and flares and the archaic Union Jacks. Quite right, too – we all have Crimplene lurking in our past and sometimes it’s fun to be reminded of it.

But this photograph was taken in one two-hundred-and-fiftieth of a second, and thus is not just about the Seventies, or 1977, or June 1977, or even the seventh of June 1977 (a Tuesday, as it happens). There’s a greater precision here. This is about 13.03 and twenty-nine seconds (give or take a few hundredths of a second) on Tuesday the seventh of June 1977, in this particular place, with the photographer crouching three yards, one foot, four and a quarter inches in front of Number 4, Cherry Gardens, Bourne Heath, Bucks.

So, tempting as it is to look at this picture for generalities, take a closer look: the single strand of hair flying up and away from this girl’s glossy fringe; the corner of a lapel bent back on that boy’s shirt; three crumbs on the table next to the plate of cakes. Take your time. You could perform an inventory of every curve and angle, every glance and gesture, their precise juxtaposition unique to this moment.

And when you do look, this photograph – like all photographs – will tease you a little. Because you can examine it all you want, you can enumerate every detail, but after a while the things you really want to know are exactly those things that are unavailable to you. There is nothing internal here; it’s all surface. You want to know what, precisely, they were thinking in that moment, what happened before the shutter opened, and after it closed. This photograph was a point on a trajectory for these people, and what it’s hiding from you is the most interesting thing of all: what happened before, what happened next.

Chapter 1

Spring 2007: What Happened Next

Satish has been awake for nineteen hours when he gets his first rest. Lying neatly on the single bed, he breathes slowly, and begins the wind-down to sleep. Without the diazepam he has to do this alone, but he has strategies. In the street outside an ambulance has just arrived; there’s the dying fall of the siren, the thunk of the doors being opened. He suspends himself between attentiveness to his sleepless condition and a carelessness of it; a small shift either way and he’ll be lost.

He starts with the breathing: in for four, hold for four, out for four, hold for four. He continues like this for a minute or two, feels his pulse rate drop, relaxes his shoulders, rolls on to his side. Here, he reminds himself, it’s crucial to keep counting the breaths. It’s when you think you’re falling asleep that you become sloppy; then you might as well open your post, read the paper, or take a shower; you won’t be sleeping any time soon.

He breathes and counts, breathes and counts. The room around him is alien. Let’s go to a different place, thinks Satish. At home, Maya will be enjoying the run of their double bed (something she will not admit, but he knows it’s true). She might be lying at a slant, one foot poking out of the covers on her own side, her head on his pillow. She will have been asleep for a long time already. His on-calls are her excuse for an early night; once, he rang home at nine o’clock and woke her.

Asha will be out cold too, he’s sure, her cheek imprinted red by the corner of a book, or striped with the tiny hairlines from the edge of the pages. Awake, she’s balanced between a young girl and a teenager, can’t wait to get on to the next thing, but sleep draws her back into childhood. Maya would rescue the book from under her, but only Satish would fold the pages the right way and bookmark it. The children are quite used to these services being performed while they sleep; Asha has never once commented. Mehul will be damply unconscious, his room filled with the loamy scent that marks the territory of boy.

Satish’s parents’ room is more of a mystery. In the delicate business of communal living, he has drawn lines to ensure everyone’s privacy and his own sanity. He trespasses now though, slipping through their door unseen. His father is asleep but his mother, liberated from the demands of the family and her own sense of obligation, sits up in bed, cardigan around her shoulders against the chill, turning the pages of a book or magazine slowly so as not to crackle them and wake her husband. One night, when Satish had returned home late, she came quickly to the bedroom door, to warn him that Mehul had been ill. Satish noticed a book lying face down on the duvet, his mother’s reading glasses on the bedside table, his father sleeping, oblivious. When his mother caught him peering at the book, she smiled. ‘Mansfield Park,’ she said, and he felt the warmth of complicity.

It’s comforting to move through the rest of the house, to hear that particular night-silence that is a sort of settling. Satish drifts down the stairs, through the hall, into the kitchen. He opens the fridge so he can see the light and hear the drip and click of it, then quietly moves across the dining room’s bare boards, and into the lounge. He lies on the broad sofa, drawing Maya’s blanket round him, cocooning himself.

Just breathing now, not counting, forgetting his earlier admonition to himself. Just breathing because snatches of nonsense are running through his brain, which is surely a good sign, fragments of sentences that mean nothing, or seem important, but when he rises up to take hold of them they skitter away. He is reaching out to Maya, pulling the blanket around himself, closing the door … he’s nearly … almost …

And then his phone is ringing. He locates it on the bedside table, eyes closed, and puts it to his ear.

‘Yes?’

‘Dr Patel. It’s the reg. She’s struggling to put in a line. Can you come?’

Satish can feel the adrenaline kick-starting him, shaking him out of his fragile doze. His hands twitch. ‘The registrar can’t get a line in?’

‘No. She’s struggling.’

‘She needs a consultant for that?’

‘Yes. Sorry. They’re in room 5.’

He wants to argue with this woman – he was so close to sleep! – but there’s no point; he’s properly awake now. He swings his legs on to the floor and reaches for his sweater. This had better be good.

An hour later, Satish returns to the bedroom, pauses, then

turns round and leaves immediately. His bladder, full from the cups of water he has drunk through the day, is swollen and prickling. But soon he is back on the narrow bed, hands folded on his chest. He thinks of the little brown bottle in his briefcase. A second dose would take the edge off, make sleep come more easily. Should he? No. No: he has rules about these things.

He starts to think about his home again, but this time it shrugs him off; it’s 3 a.m. now and there is no chance of the house shifting a little in its sleep to let him burrow in. Frustration bobs to the surface but Satish pushes it under; frustration will keep him awake.

Satish breathes and counts. He strategises. Let’s play All The Beds I’ve Ever Slept In, he thinks. All the beds.

Bed One, Kampala, although he cannot remember it. His parents’ bed, he thinks.

Bed two, Kampala. He can remember dark wood and a mosquito net, its colour intensifying as it rose above him. Did he spend much time each night, staring at that gathering of white on the ceiling? It’s an image that comes back to him effortlessly every time he plays this game. He thinks of himself, scaled down, five, four, three, lying there just as he’s lying here, staring up but breathing a different air. It was a richer air, he thinks – can this be true? – a bit of sweat, a bit of spice, the scent released from sun-warmed earth. It’s something like a kitchen-smell. But how would he know? He’s never been back; it’s an émigré’s fantasy.

Bed three, Ranjeet’s place, Bassetsbury. The weight of blankets on him, the cold a new discovery. Satish remembers the chill of the air as it entered his nostrils, his body warming it on its way down to his lungs. In Ranjeet’s house, he perfected a new way of lying in bed, falling asleep on his tummy, hands balled in fists at his neck to pin the blankets around him, a seal against the autumn night. In the morning, invariably, he would awake on his back, his shoulders and the tip of his nose cold.

Bed four, Cherry Gardens. The best nights were the rainy ones, and there were plenty of those. His dormer window was a drum, his room a sound box, and the noise kept telling him he was safe and dry, safe and warm and dry. Satish’s room was special.

Somehow he can rest here, and he does so now. He’s ten, or eleven, or twelve. His duvet quilt cover is dark blue and he lies under it, listening to the rain, not able to hear the telly downstairs because of the wet thrumming above him. He knows Mummy and Papa are in the sitting room, doing the mysterious things grown-ups do when you’re not with them.

All the kids in Cherry Gardens are asleep. Satish thinks of them, each in their own bed, sleeping tidy or sprawled, surrounded by the objects that recall them. Down the street there’s Sarah, with her make-up, her magazines and Snoopy paraphernalia. Her mother, Mrs Miller, would be downstairs making notes on a clipboard. Her dad might be fixing something.

Over the road, Mandy is sleeping. Where to start with Mandy? The contents of her secret box, he supposes, the pre-pubescent treasures spilling out of it: the leather pendant, the lipgloss, the chocolate mouse. There’s a smell to Mandy’s house, too. It’s the smell of baking. That’s what Mrs Hobbes would be doing, of course, in the kitchen. Her dad would be somewhere else. Just that: somewhere else.

Then Cai, Satish’s next-door neighbour, and his younger sister Colette. Colette … he thinks of scooters, hair bobbles, cuddly animals, generic kids’ things.

Cai, of course, had his cultural contraband, the stuff that would really piss off his dad. Satish imagines it now, sitting in the drawer waiting to be discovered. Cai’s dad – Mr Brecon – doesn’t know about it yet. He’s downstairs in the sitting room with Mrs Brecon. They’re watching It Ain’t Half Hot, Mum, and Mr Brecon is laughing and laughing …

Satish rolls over. His pillow smells nice; it smells of himself, his hair. Finally he sleeps.

Satish sleeps for four hours. He’s finally summoned to consciousness by his travel alarm, its dutiful beeps telling him: shower, handover, home.

But he can’t go home, not yet anyway, because once he’s over at the hospital his replacement rings, claiming a traffic hold-up. No one seems to need him for a bit, so Satish retreats to his office and sits, bleary, at his computer, clearing messages while he waits. He scans the subject lines: a second opinion, a paediatrics conference, the legalities of a recent firing. Towards the end, there’s something else.

It’s from Colette. The subject line says Happy and Glorious, and his fist clenches. Then he opens the email and reads what she has to say, and he can’t believe she’s saying it. It’s Colette – his friend – and she’s telling him there’s going to be a reunion, a new photograph. They want Satish to be in it. He knew it would come eventually, but he couldn’t imagine it would come from her. She’s sent him a copy of the picture. He double-clicks on the attachment.

He’s been ambushed. Four hours of sleep have not prepared him for this. And with a kick of anger he remembers how this photograph, this bloody photograph, has always ambushed him.

When he was twelve, when it all happened, he felt stalked by the thing. It first turned up in his local paper, as they had expected it to, one image in a round-up of Jubilee street parties. But it was special, you could tell even then, and the nationals got hold of it, and it started reproducing promiscuously: in broadsheets, tabloids, and a Sunday supplement souvenir edition. It lay in wait for him at school; it followed him home. His Cherry Gardens neighbours couldn’t get enough of it. They bought everything it appeared in and the newsagents kept selling out. For a few weeks it was everywhere he looked, and each time he saw it – whack! – it gave him a good thumping. People called it ‘the Jubilee photo’ or ‘that street party picture’. Its photographer, Andrew Ford, called it ‘Happy and Glorious’.

Over the years it has ambushed Satish many times because of its endlessly flexible applications. For a while it seemed central to his country’s view of itself, a snapshot of a nation in harmony. It was used – the irony! – to illustrate Britishness, or the Jubilee, or in arguments about the monarchy or multiculturalism. He remembers how politically versatile it was. It allowed racists to deny that Britain was racist (of course we aren’t: didn’t you see that lovely picture in the paper?) yet provided a neat reference to Empire, and a gentle hint that assimilation might prove a better model than multiculturalism. Here he was after all, an Asian boy happy in his white-majority Buckinghamshire village, accepted by its good-hearted people, and posing only a minimal threat to house prices.

It was used, too, by those who constructed a different story for the picture. For them, ‘Happy and Glorious’ helped to redefine what ‘English’ might mean, to posit a new normality in which your mate might be Asian, a Britain in which black immigrants were British too, and as patriotic as their white countrymen. But even these ideological tussles didn’t earn the picture its status as a National Treasure. That came later.

There’s a noise at the door, a token knock. When Satish looks up he sees Niamh, the team secretary, already halfway across the office.

‘I’ve sorted through these for you,’ she says.

‘Not now.’

‘I’m sorry.’ She stops.

‘You should knock and wait.’

‘Oh. OK.’

‘Knock and wait next time, please.’

‘I’ll remember.’

She retreats, stepping back before turning away from him. Satish stares for a few moments at the desk, at an arbitrary patch comprising the corner of his keyboard and the lid of a pen. It’s time to look at the photograph. He’s going to make himself do it. He’ll pretend he isn’t Satish at all. He’s someone else, someone detached from this entirely. This isn’t history – national, personal, familial – it’s art. He’s going to make an aesthetic judgement. Think about the composition. It’s part of the reason for the photograph’s endurance, the pleasing balance of the thing …

The photograph is taken from the head of a very long table, but with a shallow depth of field, so that only those seated nearest to the camera are in focus. Behind them, the table narrows as it

stretches away, a blurred runway of paper cups and plates and cakes and crisps and Coke.

Only six people can be seen with clarity. When Satish looks at them again he feels a rise of nausea. He finds he’s pushing his chair back, just in case he needs to leave. There’s Colette and her dad, Peter Brecon. There’s Mandy and Sarah. More to the point, here is Cai, and here he is himself, plump of cheek, his limbs already showing signs of the disproportion that will take hold of them in puberty. As the acid gathers in his stomach Satish tells himself that this is just an icon and its subjects are ciphers; they are significant only as tokens of something else. It doesn’t even look like the real world, he reminds himself, but is black and white, as all newspaper photographs were back then; he remembers newsprint coming off on his hands. And it’s thirty years old now. Look at us, he thinks. We look dated. We look funny. Don’t take this so seriously. Look at the clothes, the hair. It was long, long ago. Look at those people.

He starts with Peter Brecon. He’s nearest to the camera on the right-hand side of the table, head turned slightly away so that his face, framed by the dark curve of his comedy sideburns, is in profile. Both his arms encircle Colette. She’s grinning, kiddish, maybe six years old, and she perches on her dad’s lap, facing the camera squarely. Where was Mrs Brecon that day? She didn’t sit with the rest of the family, Satish remembers that (he remembers, too, hiding in her house, hearing her cry in her bedroom). He peers along the table and spots her – an arm, a shoulder, no more. Here, at the front of the shot, Colette is sitting stiffly upright for her moment in the spotlight. In her right hand she clutches a plastic Union Jack, a cameo of the Queen at its centre. With her left, she is pulling at the bottom of the flag, its plastic is straining at the wooden strut.

Next to them, a bit further down the table, is Sarah. She too is in profile, staring across the table at Mandy, unsmiling. Sarah’s shoulders are bare, and she’s wearing the kind of skimpy top usually seen on women whose curves would inhabit it properly. On her rangy, eleven-year-old frame it hangs loosely, its descent down her chest interrupted by the merest suggestion of breasts. Mandy, dark-eyed, shiny-lipped, meets her gaze. Neither acknowledges the camera.

Jubilee

Jubilee